Introduction...

Sir Alfred Hitchcock was perhaps one of the most famous directors and producers in the film industry. Over his career he had many successes within the horror and psychological thriller genres. Some of his most popular pictures such as Vertigo and Psycho labelled him the master of suspense. Even after Hitchcock’s passing he still has a huge influence on the industry and its professionals. Working within the silent era until the era of sound Hitchcock thrived in both British and American cinema. With a career spanning over half a century Hitchcock distinguished a specific directorial style which became easily recognisable to moviegoers. Hitchcock was not just a director but a celebrity of the film industry, fans would watch intently for his famous cameos within each of his pictures.

Early years..

Born August 13th 1899 in Leytonstone, England Alfred was the youngest child of William and Emma Hitchcock. He along with his older brother and sister had a strict Catholic upbringing. Hitchcock has said that his father once sent him to the local police station with a note asking for him to be locked in a cell for 10 minutes for bad behaviour. Hitchcock described his childhood as lonely and sheltered which was largely down to his obesity. He felt inferior to his older siblings, William and Eileen. These feelings were not helped as he witnessed his mother taking presents from his stocking and placing them into his brother and sisters one Christmas Eve. The feeling of being harshly treated would later be a recurring theme within Hitchcock’s films. Hitchcock attended Saint Ignatius College but left when he was 14 to study engineering. Hitchcock’s father died in 1914, this event had a particularly big effect on him as his father was said to be his only friend.

First job...

In 1915 Hitchcock started his first job as a technical clerk at Henley Telegraph and Cable Company. He was easily bored by this job and received many complaints about late estimates from customers. Hitchcock attended a night class on art history and began drawing, he was soon transferred to the advertising department at Henley’s where he thoroughly enjoyed and embraced his talents.

Starting out in the film industry...

Hitchcock’s involvement with the film industry began when he designed title cards for silent films. Over the time spent designing title cards Hitchcock learnt all he could about film and the industry. In 1923 he assisted director Hugh Croise with the short film Always tell your wife. When Croise was fired by producer/actor/writer Seymour Hicks Hitchcock was asked to co-direct the remaining scenes. In that same year Hitchcock was assistant director on the film Woman to Woman with Graham Cutts and producer Michael Balcon, Hitchcock also leant his hand at script writing and art direction on this picture which was a smash hit.

Hitchcock's first directing job...

Michael Balcon hired Hitchcock to direct his first film The Pleasure Garden made at UFA studios in Germany. This was a commercial failure and seriously endangered Hitchcock’s future in the film industry.

Hitchcock's first thriller picture..

Hitchcock made his debut in the thriller genre with The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1926) many consider this the start of Hitchcock’s impressive career, it also saw the introduction of the recurring themes seen throughout his films.

Alma Reville

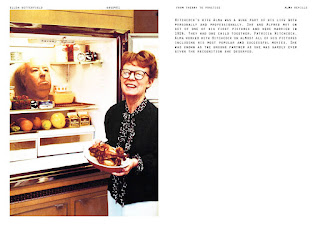

In 1926 Hitchcock married his personal assistant Alma Revile at the Brompton Oratory. Hitch met Alma on the set of Woman to Woman (1923) which she edited. Alfred admitted that he had noticed her 2 years before their collaboration but felt that her position within the company was higher than his, for two years he worked his way up to level which he felt was acceptable and he telephoned Alma and asked her of she would like to edit the film. Hitchcock proposed to Alma on a ship bringing them home from Berlin, the proposal was described by Hitchcock as ‘beautifully staged and not overplayed’.

Alma was to play a huge role within Hitchcock’s long career as she worked with him on almost every picture he directed. It is said that Alma did not receive the recognition she deserved as she was always seen as a secondary to the the great Alfred Hitchcock. Alfred and Alma’s first and only child Patricia was born 7th July 1928, she would later become an American actress and producer, she also appeared in several of her fathers films.

Timeline of films which Hitch directed..

Blackmail was released as the motion picture with sound. The climax of the film was taken on the dome of the British Museum this started Hitchcock’s tradition of using landmarks for suspense scenes in his movies.

1934 – The Man Who Knew Too Much was released, and was one of the most successful and critically acclaimed motion pictures of Hitchcock’s British period.

David O Selznick..

Hitchcock moved to America to start a seven year contract with Hollywood producer David O. Selznick. Throughout this partnership Selznick had many money problems which meant he often controlled the creative freedom within the films. They worked together until Hitchcock’s contract ended and from then on Hitchcock produced his own movies.

First American film...

Hitchcock’s first American movie, Rebecca was released which was very successful. Starring Joan Fontaine the recurring theme of the blonde damsel became more apparent and would later been seen throughout the majority of his pictures.

Salvador Dali collaboration..

Hitchcock had many collaborations throughout his career. Possibly one of the most famous was with the famous artist Salvador Dali. In 1945 Hitchcock and Dali worked together on his film Spellbound where Dali designed a dream sequence which would become very well known in the future.

Timeline of films which Hitch directed..

Notorious was released which has remained one of Hitchcock’s most acclaimed films. The plot of the movie was about Nazi’s, South America and uranium. Due to uranium being used as a plot device Hitchcock was under surveillance by the FBI.

Stage Freight was Hitchcock’s first movie for Warner Brothers which was filmed on location in the UK.

Hitchcock turned to technicolour with Dial M for Murder. This film starred Ray Milland and Grace Kelly who was a huge actress at the time, Kelly is perhaps one of the best known of Hitchcock’s blondes.

Rear Window was considered one of Hitchcock’s most thrilling and exciting pictures. The theme of voyeurism can be seen within this film as Jeff spies on his neighbours from his window. Voyeurism is associated with Hitchcock heavily due to his eccentric behaviour and treatment of his leading ladies.

Vertigo is possibly one of the best known Hitchcock films today. When it was initially released it was box office failure with the fans taking a dislike to the thriller/romance aspect of the film. This film also saw one of Hitchcock’s most famous collaborations within the design industry. Hitch worked with Saul Bass to create the film poster for Vertigo, the aesthetics of this poster has long been an inspiration for many people within the design industry.

North by Northwest was released and met with favourable results, this after the failure of Vertigo was pleasing news for Hitchcock.

Psycho was one of the most controversial of Hitchcock’s films, it is the most well known film within Hitchcock collection. Paramount were very concerned about the level of violence within certain scenes and also the nudity involved. With his wife at his side Hitchcock was able to direct these scenes and use camera shots to suggest violence and nudity without having to violate the certification standards.

Hitchcock goes against the typical motifs seen within Hollywood cinema. He kills off his main character half way through the picture which shocked many moviegoers at the time. The famous shower scene has become a widely recognised Hitchcock clip with many professionals and members of the public re-creating the scene for photos and films.

The Birds and Marnie were some of Hitchcock’s last pictures. Both starred Tippi Hedren who was one of last Hitchcock blondes. Hedren described working with Hitch as a troubling and unpleasant experience. She explains Hitch’s eccentric behaviour and the treatment he gave her. The experience of working with Hitchcock was quite disturbing for Hedren as she felt greatly controlled by the master of suspense.

.jpg)

.jpg)